A Day in the Life of T1D

Experimenting with T1D

I have been surrounded by loved ones affected by type 1 diabetes my entire life —first as a sister, and then as a mother. And while raising a child with type 1 diabetes (T1D) has certainly given me a front row seat to the challenges of managing this complicated disease, it was only this past week that I was invited to step into the shoes of a friend who has been living courageously with T1D for close to 30 years.

My friend and fellow JDRF board member casually floated the invitation on social media: “November 14 is World Diabetes Day,” Pamela began, “and I’d like to give you an inside glimpse into a few days in the life of T1D.”

It was to be an experiment. Two and a half days during which I would receive a text message every time my friend took any action related to her diabetes or even had to stop and think about managing it.

I’ll be honest: my greatest hesitation to participating in the experiment was thinking about the nights. I wondered how I would respond to being awakened in the middle of the night to a text indicating her blood sugar had dipped too low. Sleep disruption had posed significant challenges to me during the more than a dozen years when I routinely set my alarm to check my son’s overnight blood sugars. My son’s departure to college three years ago ushered in an abrupt end to this longstanding practice. Was I willing to revisit the middle of the night wake-up calls and the exhaustion that followed the next day?

Ultimately, I was more curious about the project than I was afraid of the potential sleep interruption. I shot back a private message—I’m in, and a few days later, our experiment began.

There were 26 of us in the group text, including two of our JDRF staff friends. Some already knew a lot about managing T1D, others knew quite little.

As I entered into this experiment, it immediately took on a sacred meaning for me. I knew I was being given the gift of stepping into my friend’s private world, and I was not about to take any of it for granted. I would keep my phone by my side, ringer on, and regardless of what I was doing, would reach for it the moment it signaled a message, just in case it was from her.

A new mindset

A new mindset

I was caught by surprise to discover my protective, mothering instincts kick-in for Pamela, who is more my peer than my daughter. That first night I slept restlessly, thinking throughout the night about her and wondering how she was doing. I felt an odd sense of responsibility toward her, similar in ways to what I feel for my own son. The first night gave me a visceral reminder of the strong bond that unites all of us within the T1D community, making us more like family than friends.

Of course, I expected to receive many text messages over the 60 hour period. I had managed my son’s diabetes for over a decade after all; I know how complicated it is to control. I was not surprised to receive 48 messages—it was the nature of the texts that surprised me.

When my son was very young and active and growing like a weed, his blood sugar would rise and fall dramatically throughout the day and night, causing us to spend more time reacting to them than being proactive. Managing blood sugar from a reactive approach will always set you up for more swinging blood sugar and interrupted sleep.

Surprisingly, the nights were remarkably quiet. This is not because diabetes management gets any easier as one grows into adulthood. Rather, the sheer volume of informed decisions my friend made throughout the day allowed her to have much greater glycemic control, and as a result, more restful sleep.

When my son was little, we were urged to aim for an A1C under 8% and as close to 7% as possible. Oddly, we never seemed to recalibrate his target A1C downward as he grew upward, and so even now, standing close to 6’4, he still aims for and usually achieves an A1C around 7.2%.

Pamela has an entirely different benchmark in mind. She sets her sights on an A1C of 6%, and as it turns out, there’s an incredible amount of additional proactive work required to achieve an A1C of that level (her latest A1C was an impressive 5.9%).

It immediately struck me that the majority of her texts did not focus on responses to blood sugar she was experiencing in that moment, or to a plate of food already placed before her. The overwhelming majority of her messages to us centered on proactive, preemptive thoughts about future events:

- “The stress of a travel day involving airport lines and TSA security is sure to elevate my blood sugars; better watch for it.”

- “Two days sitting in meetings all day will elevate blood sugars; I’ll put on a basal increase and check every hour to be sure it’s calculated correctly.”

- “To avoid a spike in blood sugar, I always wait fifteen minutes after a bolus of insulin before beginning to eat.”

- “I check my continuous glucose monitor every hour after a bolus of insulin, especially in the evening, to avoid being surprised by a change in blood glucose three hours later.”

- “A low blood sugar brought on an unwanted high shortly later. To stop the blood glucose swinging, I decided to eat a no-carb dinner. Blood sugar levels always influence my food choices.”

A story she shared early into the 60 hours stuck with me more than any other. At one particular meal, eaten in the airport alone, she placed her order, bolused for the meal, and began to count down the 15 minutes for her insulin to activate. But this was an airport restaurant, where people are generally in a hurry, and so in less than six minutes, the hot plate of food was placed before her.

That was going to be problematic.

There my friend sat, alone, and with a decision to make—do I eat now, before my insulin has had enough time to activate, or wait another nine minutes, just awkwardly staring at my food as it goes cold? I’m sure by now you know enough about my friend to figure out what she chose to do.

Understanding the difference

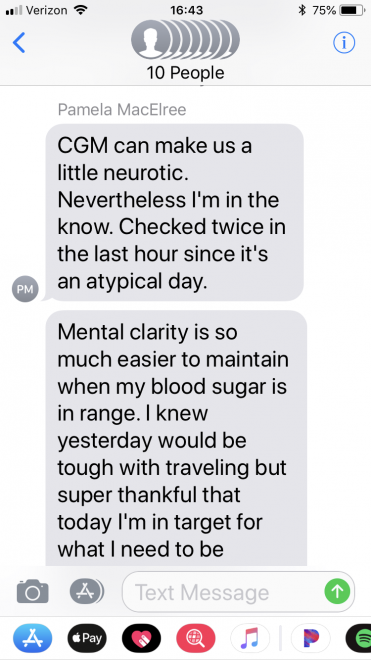

Her rationale was simple, yet struck me to the core: “Mental clarity is so much easier to maintain when my blood sugar is in range.”

The image of Pamela sitting before her hot meal, hungry, yet choosing to exercise restraint for the greater good of clear thinking later on moves me in ways I can hardly describe. It is sorrow mixed with indignation over the complexity of this disease. She chose to wait not only because the effects of elevated or swinging blood sugar is dangerous to the body in the long term, but because she knows firsthand that when her blood sugar rises too high, she cannot think clearly.

I had known that high blood sugar impacts one’s ability to think clearly, but I have never heard anyone describe it so succinctly. My son has never shared these details with me, probably out of fear I would impose blood-testing requirements before every school exam. Pamela gave me a new understanding of the mental challenges people with T1D experience. The unfairness of this disease forever rattles me in new and profound ways.

In my friend I see no trace of self-pity. She relates the facts and gives us a window into her thinking. What’s clear is that T1D is nearly always on her mind. That is what it takes to maintain such tight glycemic control. In her I see not just the strength and courage I see in so many who live with T1D. In her I see determination and grit.

And that is making all the difference.

A new mindset

A new mindset