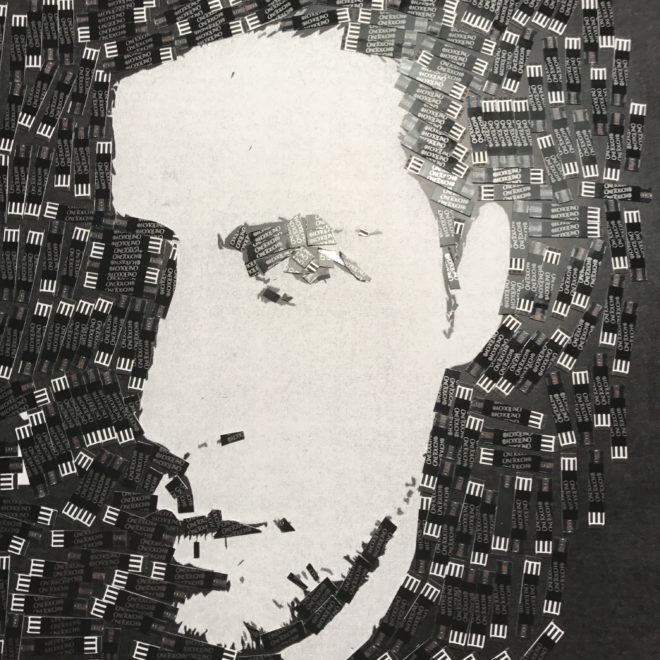

A Test Strip Self Portrait

I remember it well. Too well. There were screams of a child that woke me and after taking some time to orient, I realized I was in a hospital bed. Wires and tubes were stuck to my young body, my mouth was dry and machines buzzed and beeped all around. The yells of a little boy being wheeled past me, head covered in blood soaked gauze, have been seared into my memory. How did I get here?

In the summer months leading up to my pediatric hospitalization, I was waking up numerous times at night to urinate and chug glasses of water. I spent the days lethargic on the couch between my urgent bathroom runs. My young body was withering away. All the while, unbeknownst to neither my family nor I, dangerously high levels of acidic products were building up in my blood stream. Two weeks after my ninth birthday, my father carried me into the emergency department at Mount Sinai hospital in New York City. Intravenous lines were urgently pierced through my skin and then all went black.

Growing up with type 1 diabetes is a struggle, but it has taught me many things about myself as well. When you are forced to manage your own blood glucose levels, you learn to appreciate the elegant and complicated symphony your pancreas so graciously handles for you—until it no longer does. With no medical professionals in my family and my natural inclination towards the arts and humanities, the idea of pursuing a career in medicine never dawned on me. Type 1 diabetes opened up an intellectual passion for me that I would have never found otherwise. 22 years have passed since I awoke in that ICU bed and while I am just a few short months away from graduating from medical school, I will always be that patient before I am a doctor. As I enter into my residency training to become an endocrinologist, with long sleepless nights ahead of me, and in my most trying of moments, it will be that understanding of what it is like to be the scared patient which will carry me through. I can understand and connect with my patients because I am one.

It is because of my diabetes that I found my calling and it did something else too. I am what is known as a “non-traditional” medical student in that my background is in the arts and not the sciences. Growing up with diabetes gave me the passion for science in a way that also helped me see the overlap art plays in medicine. The delicate balance of insulin and glucose is not bland facts on a textbook page, it is elegant choreography; it is an intricate performance; it is an orchestra of infinite molecules; it is art.

Throughout medical school the two things that kept me grounded were my art and my diabetes. A sad thing happens to medical students as they progress through their education and careers: they lose their empathy. The amount of work and life sacrifices one has to endure on this journey make it difficult to remain balanced and caring toward your patients. Once again, being a person with diabetes means I am reminded on an hourly basis of what the life of a patient is like and by regularly expressing myself artistically with my drawing, I am able to find balance and come to terms with many of the difficult things we as medical professionals deal with.

Throughout medical school the two things that kept me grounded were my art and my diabetes. A sad thing happens to medical students as they progress through their education and careers: they lose their empathy. The amount of work and life sacrifices one has to endure on this journey make it difficult to remain balanced and caring toward your patients. Once again, being a person with diabetes means I am reminded on an hourly basis of what the life of a patient is like and by regularly expressing myself artistically with my drawing, I am able to find balance and come to terms with many of the difficult things we as medical professionals deal with.

My broken pancreas robbed me of many things, but it also has given me something too: a calling.

Check out other artwork for the Beyond Type 1 Express Yourself Competition and see more of his prints here!