People Are Dying from Insulin Rationing – Even TV Dramas Are Talking About It

Editor’s Note: People who take insulin require consistently affordable and predictable sources of insulin at all times. If you or a loved one are struggling to afford or access insulin, you can build custom plans based on your personal circumstances through our tool, GetInsulin.org.

Tonight, at 8 p.m. PST, Fox’s TV drama The Resident took on the timely subject matter of insulin rationing. In season 2’s episode 2, “The Prince & The Pauper,” we meet a 13-year-old girl named Abby who has type 1 diabetes and is fighting for her life. According to the script, Abby’s mother couldn’t pay the $2,000 per month out-of-pocket cost for her daughter’s diabetes supplies, despite working two jobs. Because of this, Abby starts rationing her insulin until she goes into diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). DKA occurs when the body does not receive enough insulin to break down glucose, so it starts to break down fat as fuel. Ketones are then released into the body.

Stanford endocrinologist Marina Basina describes DKA as “the most serious and life-threatening diabetes emergency. It’s characterized by severe insulin deficiency, severe hyperglycemia (high blood sugars) and increased production of counter-regulatory hormones such as glucagon, adrenaline, cortisol and growth hormone.”

“If unrecognized and untreated,” says Basina, “DKA can lead to severe dehydration, acid accumulation, altered mentation, coma and death.”

Writer of the episode and executive producer of The Resident, Andrew Chapman, who also has type 1 diabetes, explains, “We aren’t advocacy television, but we have to bring to light what is happening with insulin rationing. People need to know that this drug [insulin] isn’t about curing a disease, it is just about keeping people normal and alive, yet it’s out of reach.”

In The Resident, Abby is on a ventilator, IV and insulin drip; it’s uncertain if she’ll make it. While TV dramas have the propensity to be—well, dramatic—the details of Abby’s story are not only accurate but also more common than one might believe.

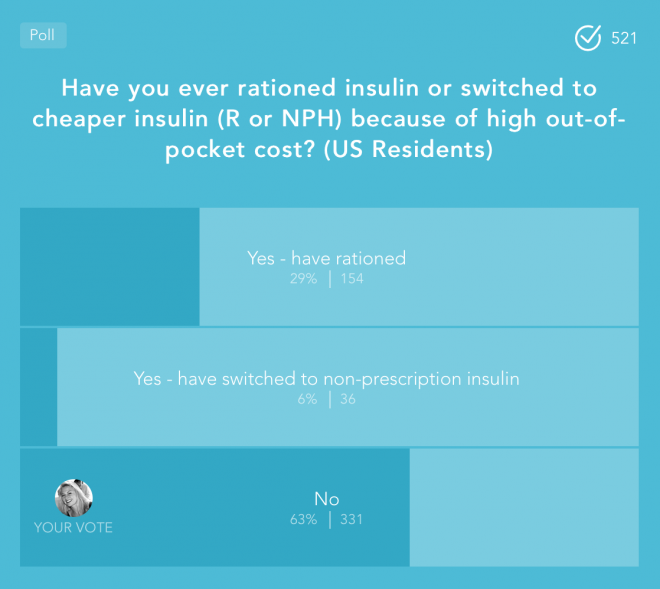

In a poll taken in the Beyond Type 1 App with more than 500 people with type 1 diabetes, nearly 30 percent said they rationed insulin because they couldn’t afford it. Another 6 percent said they switched to a non-prescription, over-the-counter insulin, which is cheaper but less effective in controlling blood sugars.

In a story that has been making headlines since June of last year, Alec Smith from Minnesota didn’t qualify to stay on his mother’s health insurance when he turned 26 years old. As a manager of a Mongolian BBQ restaurant he brought in roughly $2,200 a month. This would have been a livable wage except that he also had the chronic illness of type 1 diabetes. His monthly supplies cost him $1,300, more than half of his paycheck.

According to his mother, Nicole Smith-Holt, they shopped around for insurance plans, but Alec couldn’t afford any of them with the high deductibles. He decided to pay out-of-pocket, being the cheapest option, until he could save enough for a better insurance policy.

“That was the plan,” Smith-Holt said, “but he was never able to even make his first purchase. He didn’t have the $1,300 the first time he went to the pharmacy to pick up his refill. He was planning on coming back in a couple days because he was rationing his insulin with whatever he had left to hopefully get him through until then. He didn’t make it that long.”

Twenty-seven days after losing insurance, Alec died.

Like Abby, he had the classic symptoms of DKA due to rationing his insulin supply. Alec had put himself on a low-carb diet that required less insulin, but despite that, was experiencing shortness of breath, abdominal pain, blurry vision and vomiting.

According to Dr. Silvio Inzucchi from the Yale Diabetes Center, when someone with type 1 diabetes doesn’t receive insulin, “they’ll begin to fall ill within 12-24 hours after last insulin injection, depending on its duration of effect. Within 24-48 hours they’ll be in DKA. Beyond that, mortal outcomes would likely occur within days to perhaps a week or two” (Healthline).

But the danger of rationing insulin is both short-term and long-term. “The short-term is the danger of going into DKA,” says Basina, MD, “The long-term danger is developing complications of diabetes such as heart disease, nerve, kidney and eye problems as well as recurrent infections.

That means that rationing insulin has the potential to kill someone with type 1 diabetes immediately, or there’s the outcome of it dramatically shortening their life.

Smith-Holt told Beyond Type 1, “I have been hearing more stories like Alec’s. The more his story gets out there, the more people contact me and tell me that their loved ones passed away this way, because they couldn’t afford their insulin, or their family member has filed bankruptcy. It’s just heartbreaking.”

Insulin was discovered in 1921 and its patent sold for $1 to the University of Toronto in the hope that no company would have a monopoly on it and that people with type 1 diabetes could have affordable access to it. Nearly 100 years later, that doesn’t seem to be the case, at least not in the United States.

Since 1996, the “big three” insulin manufacturers Lilly, Sanofi and Novo Nordisk have increased the list price of insulin in lock-step by 1,123 percent. Although insulin manufacturers have blamed pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) as well as health insurers for the rising cost of insulin, it appears to be a problem complicated by all parties involved.

“While the insulin supply mirrors that of many other prescription medications,” says Greg Brown in The Insulin Pricing Machine, “the ADA reported that it was not possible to pinpoint any specific reasons for the surge in prices.”

Seeing the insulin rationing drama unfold in The Resident suggests that people are at least taking notice of the problem, though it doesn’t offer much hope for a solution in the near future.

Basina offers that “each pharmaceutical insulin-making company has a program for compassionate insulin. You can ask your healthcare provider to help you with filling out an application form and if you qualify from income standpoint, you will get approved for a year supply of insulin.”

Not everyone qualifies for these discount programs though. Another option is to buy NPH insulin over-the-counter when in an emergency and a patient is unwilling to go—or unable to afford going—to the emergency room. This is not a long-term solution though, as NPH has a delayed peak time and stays in the system longer, making blood glucose control difficult, leading to variability and poor outcomes.

Chapman from The Resident says, “Often in television shows and movies we use people with diabetes as a plot device—they need insulin or they’re going to die, they need orange juice or they’re going to die—it is an easy red herring, flimsy plot device to add drama. We wanted to show it as a real thing, like these are the issues that diabetics struggle with and that diabetics are real people.”

Abby is a fictionalized character, but maybe she’s the very thing needed to bring this issue to the forefront. If art is a reflection of society, then this TV drama is holding up the mirror that we all need to see.

Read Who will profit from the cure of Type 1 diabetes? By Dana Howe