Summiting Kazbek: A T1D Story

Written by: Pavel Rozens

8 minute read

January 17, 2019

Editor’s Note: Pavel Rozens, the Type One Run chapter leader in Riga, Latvia, celebrated his 30th birthday by climbing Kazbek, one of the largest mountains in the world.

Day 1

At 21, I was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes. I celebrated my 30th birthday with an amazing gift: scaling Kazbek. At 5047 meters above sea level, it is the seventh highest peak in Europe. At the base, it’s 25°C degrees during the day and 10°C at night. At the peak, it is -10°C degrees during the day, and I do not want to know what it is at night…

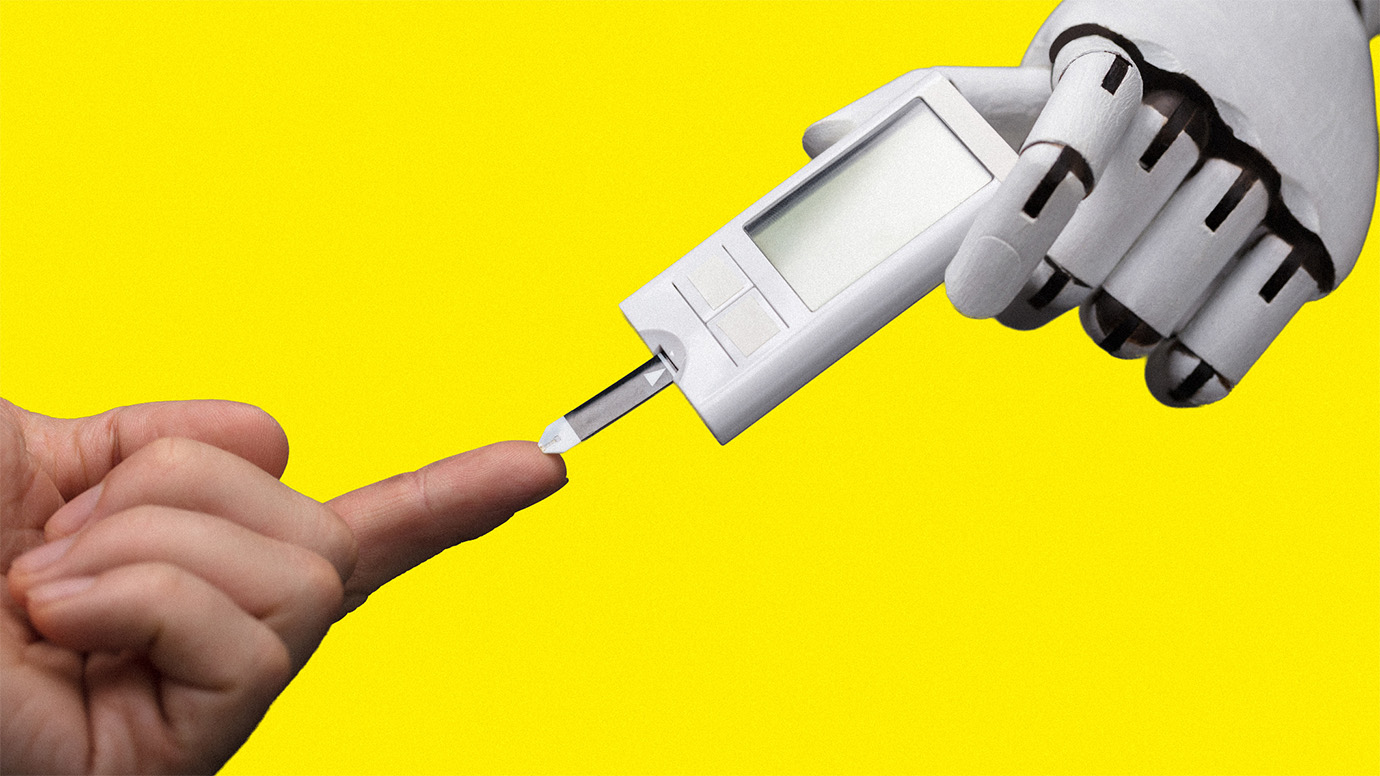

My backpack weighed around 27kg. There were two of us: a small girl, Nino and me, and George would join us at the base camp. None of us had ever been there, or at that altitude, and we were not experienced in ascending peaks. We planned to ascend in six days, slowly increasing height by 500-700 meters, and descend in one day. We did our homework, our backpacks were well thought out, with equipment attached. We had three sets of diabetic necessities. In each one was insulin, a glucometer, strips, glucagon, several spare glucometers and visual strips. My main glucometer Contour Plus was from Bayer and was said to work up to 6200 meters and 5C°. It was the only gadget for measuring blood glucose levels that I was able to find that would work with such extremities. Besides this, I had Bounty Bars and various medications.

Why did I need all of this? When I got diagnosed, I decided that if I could control diabetes while hiking, it would be much easier in the city. I started hiking, working up to week-long treks. I was drawn further and further—working out daily, biking, participating in half-marathons. I believe that you should do things that scare you, since they motivate you to become better, you are afraid, and you work on it and prepare yourself. On the evening of August 25th, my birthday, instead of drinking and partying, we were slowly hiking up a mountain towards a monastery. In that moment, I knew I was stronger and better than I was six months before.

Day 2

Day 2

According to our plan, on August 26th, we should have moved from the Sameba monastery (2170 meters) to the first camp at Sabertse (2900 meters). However, I developed symptoms of nausea and vomiting. The latter is one of the scariest parts of altitude sickness, as it exhausts you, decreases blood sugar levels and makes it impossible to increase them without a glucagon. I was just not able to believe that this was it, I’d gotten altitude sickness at such a low altitude—impossible! We walked 500 meters to the shadows for camping and I slept there the whole day. In the evening, I felt much better and life became much brighter. While I was sleeping, two German girls and two guys from Moscow joined our camp. Later, two Turkish guys joined us, as well as a 59-year-old Ukrainian who was climbing alone. We had one more guest—a shepherd dog—who spent the whole night with us. Dogs around the monastery act as if each camp is their home and they guard it from cows and strangers. They are always kind to people, feeling that they are needed, and that they are in a right place. Here in this company, by the campfire in the fog, we spent the evening. I was so glad not to be sick and to know we could continue to climb.

Day 3

We got up at 6am, fed the dog, and started hiking. We decided to go straight to Meteo—this meant 1,500 meters more of altitude and around 8-10 hours of hiking. For every hour of hiking, I ate half a bar. I tried to keep my sugar at 144 mg/dL8 mmol/L, but of course it sometimes tries to run up or down. I injected a low dose of insulin at lunch so I could burn it along the way. A set of insulin pens, glucometer and a glucagon hung around my neck in a waterproof Ziploc and Nino had my spare pack. Another large supply of insulin and an additional glucometer were in a waterproof bag in my backpack. At night, all this stuff lived in my sleeping bag. I constantly checked Nino: “Where is my kit?” My fear was frozen insulin—a glucometer can be heated, but not insulin.

There were more than a hundred tents in total once we reached Meteo. We set up one as fast as we could next to a group from Russia and went to the kitchen. The Betlemi hut is a building with a multi-colored facade, at an altitude of 3673 meters. It is a haven for climbers. The place is like a spaceship frozen in time, an island cut off by a glacier. Inside there are several living rooms with bunk beds, a guide room, and a kitchen. The kitchen is crowded—everyone sits right next to each other. There are Czechs, Poles, Russians, Ukrainians, Lithuanians, Dutchmen, Germans, Italians and so on. We were hospitably invited for a dinner by friends of George. It consisted of rice porridge, chocolates, cheese and sausages. All the walls were full of stickers of sport tourism agencies and phrases. There was no free space, even the ceiling was decorated with flags. Sadly, there were a couple of announcements of missing people too.

It was hard to breathe here for two reasons: the first is the altitude. When you walk to the kitchen, you get short of breath as if you had run there wearing a heavy backpack. The second reason is the dry thin air filled with dust from rocks. Absolutely everything is covered in dust there, our tent was filled with dust after a couple of hours. Half of the people have pharyngitis cough here. Nino was at Meteo three years ago and says that absolutely nothing has changed. After preparing ourselves, tying the tent to the stones, arranging things, and trying to fit 50 kg of our stuff and two bodies into a tiny tent weighing 2.2 kg, we finally fell asleep.

Day 4

For half a day we just rested. My blood sugar levels began to increase on their own, and I started injecting a unit of insulin every hour, which helped. This was to be expected, I had heard that for many people with diabetes, the need for insulin after 3000 meters increases.

We learned that the next two days would be thunderstorms. This means that our plan, to move the camp to the plateau tomorrow and then ascend, would not happen, as we would be stuck on the plateau in the storm. The prospect of sitting in a storm in an open ice plate, blown by winds and waiting for good weather, did not appeal to us. With news of the weather forecast, the camp became more alive. Some started to move to the plateau fast, some started to prepare to go climbing at night. We felt we had neither the strength nor the time machine to prepare for a six-hour hike that evening, but the atmosphere was fueled by people coming down from the mountain and showing us their perfect photos. We talked with George, and after some thinking and discussion, we decided to go earlier than planned in a bundle of four people. We gathered things quickly and went to bed at 7p.m. The alarm clock would wake us at 12 a.m., before the storm began at 2 a.m.

Day 5

We woke up with the alarm at 12 a.m. The wind brutally ruffled the tent and I had no desire to summit. But we stuck to our plan anyways. The locals said that no, the wind was not a gift, but that the ascent was possible and would get calmer. We went out in complete darkness. Immediately, my face began to pinch from the cold, and a couple of hours later, I had heartburn and a headache. In my daily life, my blood sugar is usually at 120.6 mg/dL6.7 mmol/L. I am a reasonable diabetic, but now my levels crawled up from the usual hiking levels of 8-10 to 13-15. I took pills for my symptoms, injected insulin and went further. I tried to breathe deeply, as much as the temperature allowed. An hour later, all my unpleasant symptoms were gone—apparently my choice of pills paid off. In the pitch darkness, a serpent of more than fifty lanterns rose up the mountain. Every light was a person who came to look for something inside of himself here. We stubbornly climbed up against the cold, wind and fatigue. Four hours later, we got to the glacier. I do not really have proper boots for this trip, but my socks for -30°C cold were a savior—the only thing better than these socks would be a cat, a blanket and coffee with cognac at home.

We reached the plateau, and the distance from us to the groups ahead of us seemed frightening. They were so high, like crawling dots. The footpath was narrow, with a width of two feet going upstairs in a zigzag. On the one side—the mountain wall, and on the other—the downward abyss. It was getting harder to go with each step. We had been hiking already about six hours. The water in the drinking systems was frozen, I gave Nino tea and tried to cheat my own thirst with chewing gum and cough drops. The pace of our group had slowed. With a turtle’s steps, we reached the “saddle.” Kazbek has two heads, and a so-called saddle between them. It was warm, the sun was shining and there is a whole group of colorful people in the snow enjoying the view and resting. The weather had spared us: there was no wind or clouds. Later, one of the guides said that these were the best days of the season, and that seven of his last twelve groups had not reached summit, for weather or physiological reasons.

We reached the plateau, and the distance from us to the groups ahead of us seemed frightening. They were so high, like crawling dots. The footpath was narrow, with a width of two feet going upstairs in a zigzag. On the one side—the mountain wall, and on the other—the downward abyss. It was getting harder to go with each step. We had been hiking already about six hours. The water in the drinking systems was frozen, I gave Nino tea and tried to cheat my own thirst with chewing gum and cough drops. The pace of our group had slowed. With a turtle’s steps, we reached the “saddle.” Kazbek has two heads, and a so-called saddle between them. It was warm, the sun was shining and there is a whole group of colorful people in the snow enjoying the view and resting. The weather had spared us: there was no wind or clouds. Later, one of the guides said that these were the best days of the season, and that seven of his last twelve groups had not reached summit, for weather or physiological reasons.

We left the backpacks in the snow and took the final hike at our snail pace. The Chinese proverb says: “Quickly—it is slow, but without stopping.” The last stage took us another hour, but we made it! We reached the top, we had made it to Kazbek. This was not the road of a seven-hour hike, or four days from the foot of a mountain. This was a half-year road from the moment the idea was born in my kitchen, up until the last step to the top. We did not find a single person with type 1 diabetes (T1D) who was summiting Kazbek and have no knowledge of anyone who has done it with T1D. Stunned and happy, we looked at each other. I had two posters with me that said, “F*** You Diabetes” and “My Diabetes My Rules”—it was hard to choose.

Descending was more unpleasant than ascending, as it’s more traumatic and there’s more stress on the joints. The discomfort had come back, it felt like I had a heavy hangover. We slowly descended, the sun warmed and the water in the pipe of the system melted down, and only then I realized how much I wanted to drink. Since the only option was to descend, we had our favorite cocktail—medications, painkillers, injected insulin for my blood sugar at 10—and hiked down. The water ran out after three hours, and we got another round of thirst. It is said that in the mountains, dehydration happens faster, as the lungs evaporate moisture in the rarefied air. It dries everything up, makes lips crack and inflames nostrils. After being in this state for nine hours, we made it to Meteo. We ate and I drank three liters of water. I chatted with some Czechs and we drank strong moonshine for our mutual success.

Days 6 and 7

We descended from the glacier quite easily and were already imagining what we would eat for dinner. Our dreams faded when we came to the place where we met George on the way here. That day was colder, and now it was much warmer, causing the glacier to melt. The stream turned into a raging one, carrying boulders; it almost pulled out a trekking pole from hands when I looked for the bottom in it. We stood and wondered for a long time: to jump or not to jump, and what would be the best way to secure us? In the end, we decided not to jump. Three Polish girls came, and two decided to jump. One went smoothly, but the other slipped. She was dragged by a stream of about five meters until she was caught by her friend. We decided that we made the right decision finding a way around.

We set up a tent at a camping place next to the other mountaineers. We successfully found wood, protected the place for the campfire with flat stones, and for about 30 minutes we tried to make a fire. At an altitude of about 3,000 meters, everything burned with difficulty, only the wrappers from Bounty bars burned well, and helped us to light up campfire. We looked at the stars, drank beer and finally, did not have to hurry anywhere. It remained only about three to four hours more of descending and then we would be in the village, in a cafe, waiting for our lunch, and looking at ourselves in the mirror behind the bar.

Reflecting

Overall, this journey influenced my feelings about compensating for diabetes. After spending a week hiking, it is much easier for me to plan my meals and stick to it, to keep in mind the chain of diabetic decisions. It seems to me that these are very important skills, being able to plan and evaluate risks. I learned how to plan for negative situations. I learned to say with pride that I have diabetes. The most important thing that diabetes has given me is consciousness. Death is the only 100 percent guarantee that we have in life, and it motivates to live an interesting life here and now, to fight, to not waste time on nonsense. Do something that brings you joy and makes you better. Live for today.

Author

Pavel Rozens

Pavel Rozens is the Type One Run chapter leader in Riga, Latvia. His passions include hiking, traveling, reading and good literature.

Related Resources

The American Diabetes Association’s 2025 Scientific Sessions in Chicago were full of fresh ideas and...

Read more

A diabetes diagnosis doesn’t mean your sex life is off-limits. It's still yours to enjoy—just...

Read more

Insulin is the main hormone your body uses to control how much sugar is in...

Read more