How Insulin Pricing Works in the U.S.

Editor’s Note: People who take insulin require consistently affordable and predictable sources of insulin at all times. If you or a loved one are struggling to afford or access insulin, click here.

How did insulin become so expensive in the United States? The American healthcare system is made up of a complex web of players who exchange money for pharmaceutical products in ways that are not entirely clear to consumers. This makes it difficult to know who to blame. Indeed, they often blame each other for the high cost of insulin.

When everyone is confused and pointing fingers, nobody knows how to fix the problem, and the status quo reigns. So let’s dive into the issue of insulin pricing and figure out who these players are, how the money flows and what this means for patients.

The players

There are four major players in the insulin pricing system:

1. Pharmaceutical companies

2. Insurance companies

3. Pharmacy benefit managers

4. The government

Each one has a distinct role, but they are all intertwined in ways that result in the prices consumers see.

Pharmaceutical companies

You may have heard of the “Big Three” insulin manufacturers who account for more than 90 percent of the global insulin market: Eli Lilly (Humalog, Basaglar), NovoNordisk (Novolog, Levemir) and Sanofi Aventis (Lantus). The “Big Three” have been accused of price-fixing, as they have a trend of raising prices of insulin in lockstep with one another.

Pharmaceutical companies set the list price for insulin, and are incentivized by profits to continue to raise those prices. For these companies, the price of insulin is a business decision.

Insurance companies

Health insurance companies pay for a portion of the drug cost, depending on the policy the patient holds. For patients with health insurance, the coverage they receive can reduce the out-of-pocket cost of insulin relative to the price at the pharmacy. With health insurance, patients pay a monthly premium in order to be a member of the plan, and any additional costs they incur during their plan year are capped at a specified out-of-pocket limit.

Prescription drugs may or may not contribute toward the plan’s deductible (the amount a patient spends in addition to premiums before the plan covers all costs), and many plans have a list of preferred drugs called a formulary. Insulin is often in the 2nd or 3rd tier of the formulary, meaning that patients pay more for this drug than for something in the 1st tier.

In addition to cost-sharing with patients, the insurance companies receive rebates from the pharmaceutical companies via the pharmacy benefit managers.

Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs)

Pharmacy benefit managers, or PBMs, are the player that is hidden in plain sight. The three largest PBMs are Express Scripts, CVS Caremark and OptumRX. PBMs are third-party intermediaries who negotiate prices between pharmaceutical companies and insurance companies. However, the lines between insurance companies and PBMs are becoming increasingly blurred—OptumRx is owned by United Healthcare, Cigna recently merged with Express Scripts and CVS Health acquired Aetna.

PBMs’ stated goal is to reduce costs from pharmaceuticals for the insurance companies while improving health outcomes for the members of the insurance plans. They participate in the rebate system and take a share of the profits from prescriptions that are sold to members of the insurance plans.

This group is often invisible to consumers and can drive up the costs of prescriptions without consumer awareness.

Government

While the U.S. healthcare system is generally part of our free market economy, there are ways that the government is involved. The government regulates pharmaceutical patents and FDA approvals for drugs and devices, but it does not currently play a role in regulating pricing.

The patent regulation is a key component of how prescription drug prices remain high. Patents are valid for a set period of time, and once they expire, generic versions of these medications can be sold for significantly lower prices than the name brand versions. However, if there is a change to the formula (any change, not necessarily an improvement), the patent can be renewed for an additional term, thereby delaying the release of generics.

When insulin patents are continually renewed, prices continue to rise because there are no generics on the market to compete with the name brand products. Along the lines of generic drugs, there is another class called biosimilar drugs, which have different chemical formulas but produce the same effect in the body. There have been lawsuits preventing biosimilar insulins from being sold in the US.

In some instances—like Medicaid for people with financial need, and Medicare for the elderly and disabled—the U.S. Government functions as an insurance company.

In early 2019, there was a call for the government to intervene in regulating the price of insulin and other prescription drugs, and some politicians spoke out, held hearings and sent inquiries to manufacturers.

The system

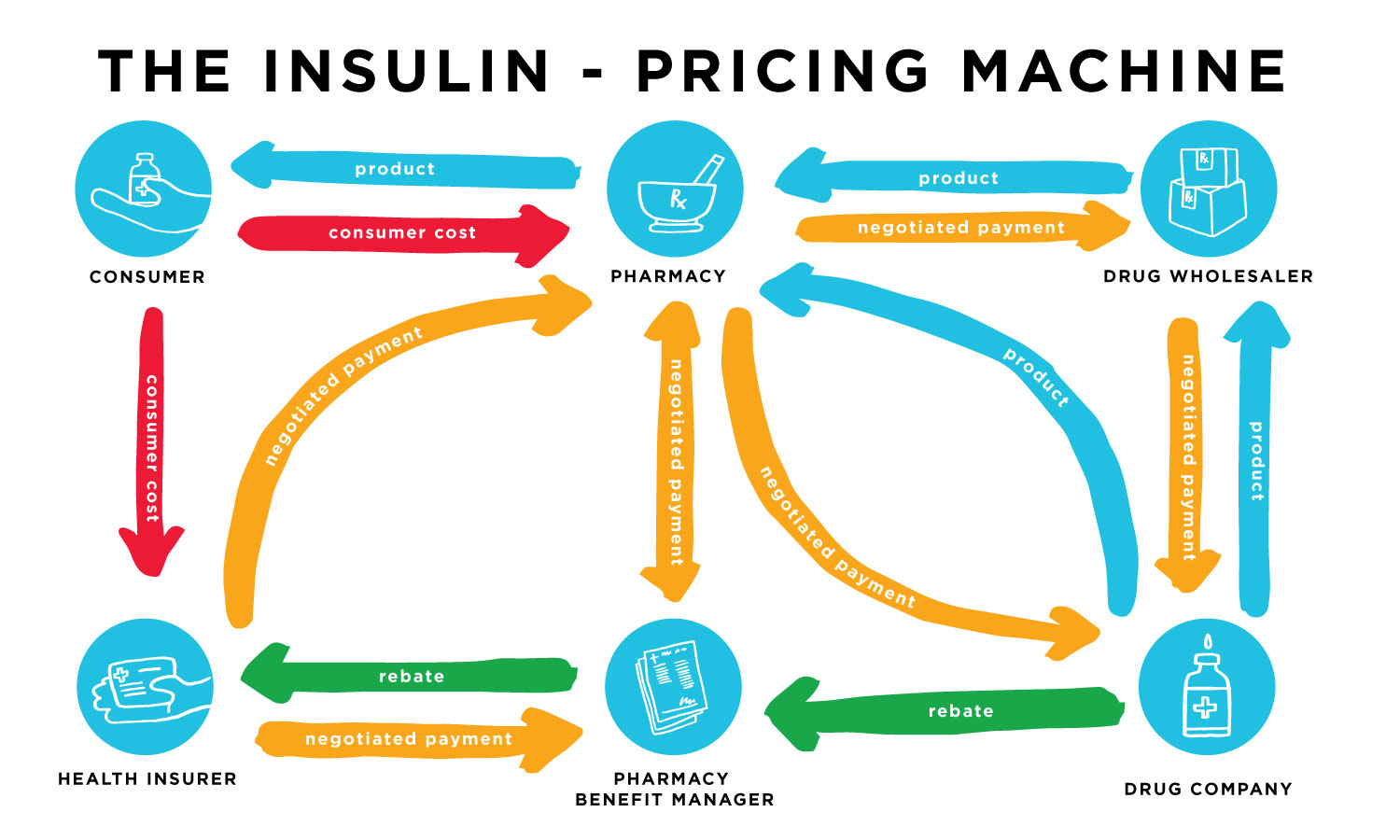

There is a complex web of rebates and discounts between the pharmaceutical manufacturers and other entities taking place before and after the insulin reaches the patient.

One major rebate impacting our system is paid from insulin manufacturers to PBMs. Manufacturers actually pay a percentage of the list price back to PBMs when the PBM agrees to list a specific drug on insurance plans. Effectively, the PBM gets a deep discount on drugs in return for making them available through insurance.

This sets up a reverse incentive for manufacturers and explains why competition in the insulin market has historically led to higher list prices. Higher list prices = higher rebates to PBMs.

Rebates between manufacturers and PBMs are hardly the end of the story. Let’s explore this web a bit further.

Insulin arrives at the pharmacy either directly from the pharmaceutical company or through a prescription drug wholesaler. There are negotiated payments from the wholesaler to the drug company, from the pharmacy to the wholesaler or drug company, from the insurance company to the pharmacy, from the insurance company to the PBM, and between the pharmacy and the PBM.

Then there are the rebates the drug companies give to the PBM and the PBM gives a portion of that rebate to the insurance company. This all changes the cost from the time the insulin leaves the manufacturer until it reaches the customer at a retail pharmacy.

Customers pay at the pharmacy when they receive their medications, and if they have health insurance, they are responsible for the co-payment and premiums. Depending on the insurance plan, prescription drug costs may or may not contribute toward the deductible, but they do count toward the out-of-pocket limit.

These plans and rates are not standardized, so people who need insulin end up paying a wide range of prices when they pick up their medication at the pharmacy.

The consumer cost is affected by all of these behind-the-scenes negotiations and rebates because there are five parties making money from a single transaction.

Where does that leave us?

Insulin pricing in the United States is unfortunately only one example of the complexity of a for-profit healthcare system. There is no doubt that people with any kind of diabetes who need insulin to live face difficult choices when navigating this system, and it is unjust that an ability to pay for a drug is often the determining factor for their quality of care.

If reading this made your head spin and you’re looking for ways to make a difference, find out more about how you can get involved with access advocacy in the USA.

If you or someone you know needs help getting insulin, click here. For a more in-depth look at insulin-pricing, read The Insulin-Pricing Machine.