Playing Ball with Low Blood Sugar

I was an athlete, and then diabetes made me weak.

I was diagnosed at 15, and though I continued to play sports for years afterwards, I never acknowledged this weakness. My coaches saw it, my family saw it and eventually I saw it: for me, diabetes was bleeding sports of their joy. I didn’t admit it to myself at first—that I was weaker—and that was my mistake. If you admit the weakness you can deal with it. If you don’t, you declare a cold war on your own body.

There are some professional athletes with type 1 diabetes, people who drag the added weight of their disease behind them. NFL quarterback Jay Cutler and NBA draft bust Adam Morrison are among the most famous. Their success tells us that diabetes doesn’t erect an insurmountable barrier against the dream of becoming a pro athlete. Which is encouraging. You can still be almost anything as a person with diabetes (excluding pilot and truck driver). But that doesn’t mean it’s easy. Cutler and Morrison had to stare at their disadvantages without blinking, and then work harder than everyone else.

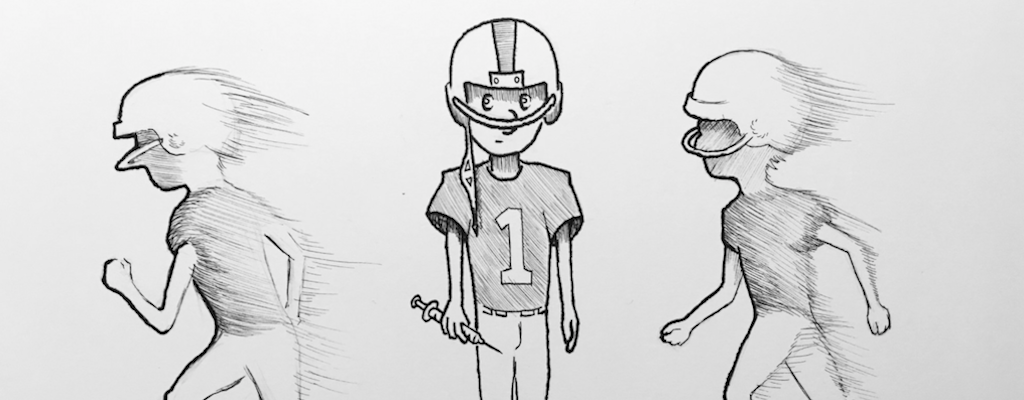

When I was 15, in my sophomore year of high school, I played three sports: football, basketball and baseball, and I took great joy in them. Then I was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes. After my diagnosis in the fall of that year, everything got harder. I had to guard against low blood sugars, carrying ungainly bottles of glucose tablets with me everywhere: a slight dip in blood sugar could knock me out of a game for half an hour. I had to defend myself from high blood sugars, which sap energy and morale.

Soon I quit football. The squalor and toil of practices made it difficult to find time to check my blood sugar, and it was tough to keep my syringes out of the mud. If I became too low or too high to practice, I’d stand on the sidelines while my teammates whipped past. If this happened while the team was running suicides, my popularity on the team would understandably diminish. Each time I trotted to the sidelines to monitor my diabetes, I severed another thread of connective tissue between me and the team. I had no great love for football, however, and it was easy to quit.

I was unwilling to give up on basketball so easily. I loved it. But basketball is a tricky sport to play with diabetes. Its intense cardiovascular demands can torpedo a diabetic’s blood sugar in a few minutes. This recovery time can cost the person with diabetes a great deal of playing time, especially with the game’s frenetic pace. So playing ball with diabetes was going to be tough.

My coaches knew this. Sort of. Before tryouts I told them about my diabetes, and they seemed to understand. But they were preparing to accommodate an athlete with a medical asterisk, and I could imagine how uncomfortable this made them. Soon it became clear that they didn’t know how to handle a person with diabetes on the court.

During a practice, we were running three-man-weave drills, and as I trotted back up the court to rejoin the line, I noticed my hands were shaking. I didn’t feel low, but sometimes the symptoms of hypoglycemia precede the feeling of dread. I held my hand up to my face to see how badly it was shaking, and the coaches saw this; immediately they were yelling.

“No, not good! Not what we want to see!”

The awkwardness and imprecision of their words suggested to me, as I left the drill, that they didn’t really know what they were mad at. They didn’t know what diabetes was, really. They just knew that whatever it was, it was bad.

They seemed a little scared, too. Diabetes must have seemed like a big liability. Maybe they knew about Adam Morrison, who had a diabetic seizure during a basketball game in eighth grade. They kept glaring at me with an inscrutable mixture of protectiveness and resentment.

Sitting against the wall, I checked my blood sugar. My teammates stole glances at me and turned away with polite faux-neglect. I looked at my meter. I was not low. Angry with myself, I tried to rejoin the drill, but the coaches wouldn’t let me.

This episode suggested to me the breadth of the sacrifices athletes with diabetes must make. Athletes like Jay Cutler and Adam Morrison don’t just leave the game when they feel ill, they have to leave the game when they feel any kind of weirdness. And even if there’s no weirdness, they still have to leave the game periodically just to make sure everything’s okay. That’s not something any other athlete has to deal with.

When you play sports with this disease, you must discover a balance between caution and recklessness: when to stay in the game, when to leave, when to trust yourself. The problem is that that balance doesn’t really exist. Changes in blood sugar, much like the vicissitudes of a football or basketball game, can never be adequately predicted. Playing sports with diabetes isn’t an equation to solve; it’s an evil to be endured. Back when I still played sports, I didn’t know this.

The last time I played sports with type 1 diabetes, I was with a traveling baseball team, playing in a summer league as a pitcher.

When the season began, I was firmly in the starting rotation, usually pitching two or three innings every other game and acquitting myself reasonably well. I garnered a few wins. The coach seemed to like me. At some point, which I don’t remember, I must have been checking my blood sugar in the dugout with a meter on my lap. He asked me what I was doing, and I told him about being a person with diabetes. He nodded, stared at the meter some and walked away. I thought little of it.

After that revelation, though, I didn’t pitch another inning. He would promise me a start days in advance, but when the day came, he’d renege as I walked to the bullpen to warm up. For the rest of the summer, my jersey stayed innocent of dust. When he ran out of pitchers, he’d look right past me and put a shortstop on the mound. I never played competitive baseball again.

I was angry, but part of me understood the coach’s decision. Many of his players would only attend college via baseball scholarship, and the reputation of his program would depend on the quality of those college programs to which he sent his players. Each time he sent someone onto the field bearing his team’s jersey, he was investing his reputation in them. Any sign of weakness would signal to him that this player wouldn’t reward that investment.

So, he penalized any player who showed frailty. A first-baseman suffered heatstroke in practice and, after that, rode pine for the rest of the summer. Another kid cried after his pitching cost us a game, and the coach benched and berated him until he quit the team. The coach was running a business; he wouldn’t accept weakness in his workers. In his eyes, diabetes was unforgivable.

And while my benching was disappointing, it drove home the idea that I was weaker through diabetes, and could not pretend otherwise. Diabetes was a liability to the team, and it was my job to deal with that, not the coach’s.

My brother Mason (also a person with diabetes) runs marathons, and he also studies the biological consequences of living and exercising with diabetes. As a runner and a scientist, he knows very well that the disease puts him at several disadvantages. Not only does he have to carry a pack for his gear, adding extra weight, and check his blood sugar regularly while running, his diabetic body is also inherently worse at handling the stresses of cardiovascular activity. His blood vessels (and mine) are too tense, and distribute blood to the necessary muscles poorly. Put another way, people with diabetes typically won’t achieve the same level of fitness as a non-diabetic, even with equivalent training.

Mason challenges these weaknesses head on, and sometimes it looks as though he stomps diabetes’ throat into the dust: he places highly in races and earns medals. But prior to any triumph, he must plan everything meticulously in order to merely participate: calculating precise meals, scanning his blood sugars with a continuous glucose monitor and never giving himself an off-day.

Mason’s example, coupled with my own experience, has taught me that athletes with diabetes must do two things. First, they must admit to themselves that they’re at a disadvantage. Second, once athletes with diabetes accustom themselves to the idea of their own frailty, they must plan accordingly.

Both things are tricky, and I never mastered either of them. Diabetes deflates the illusions of endless youth and youthful invincibility, which happen to be the illusions of the confident athlete. It’s tough to preserve your on-field swagger when you know the body of your opponent functions more adequately than yours in measurable ways.

When I played sports in high school I possessed the garden-variety teenage arrogance that believed my talent would transcend limitations. Diabetes couldn’t stop me, I thought, but its indifferent poison crept through my limbs anyway. Now I know what I have to endure, and my admiration for athletes with diabetes who didn’t quit has deepened. My own stubborn ignorance back in high school throws their gritty humility into sharp relief, and now when I watch them, I can enjoy the little triumphs nobody else knows about, and savor the astonishment of their damaged bodies chasing grace.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published on Folks.