Insurance Company Conduct Negatively Impacts T1D Patient

Editor’s Note: Jess has since reached out to her congressman, Rep. Ryan Costello. Through multiple communications with one of his aides, she’s gotten UHC to agree to full coverage of a loaner pump when her current pump breaks, but they did not agree to replace it until it breaks.

If you pay for health insurance in the US, you most likely have experienced, or have heard of someone who has had difficulty with health insurance companies paying for what was agreed upon. Everyone knows it’s bad business to promise something you don’t deliver. In this case, it leaves customers more than dissatisfied—it puts their lives at risk. These corporations aren’t selling pizza; they’re selling access to life-saving and life-preserving medicine and devices. In light of that, shouldn’t there be a higher standard of ethics in how health insurance companies conduct business with their customers? When they act negligently or deceptively, shouldn’t they be held accountable like any other industry? We think so.

#GETJESSAPUMP

Meet Jessica Hoffer. She has an auto-immune disease called type 1 diabetes. Her own body killed off the healthy insulin-producing cells in her pancreas, making her insulin-dependent for life. She’s an occupational therapist in Pennsylvania. She has two jobs: the first working with Early Intervention helping children under the age of 3 who present developmental delays. The second is at a residential center for adults with severe cognitive disabilities. With two part-time jobs she’d have to pay out of pocket for her insurance or depend on government assistance through the ACA. Luckily, her husband has full-time employment, with benefits, giving her coverage under UnitedHealthcare Insurance.

When Jessica was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes in April of 2008, she was started on shots, using both long and short-acting insulin to stabilize her blood sugars and survive. Just four months into this therapy, her blood sugars were erratic, rendering her unable to complete daily activities safely. In response, her doctors prescribed her an Animas insulin pump to help improve her management, and it worked.

In September of 2016, the warranty on her pump expired after four years of use, which is industry standard.

Her doctor wrote her insurance company, UHC, a Letter of Medical Necessity for a pre-authorization for a replacement, because having an insulin pump is vital to Jessica’s medical care. Here’s what happened next:

Lost documents

A month after her doctor submitted the letter, Jessica contacted UHC and was told no such document had been received. Her doctor sent another one. When Jessica called to see if the second one had been received, she got the same response. UHC lost or did not receive the Letter of Medical Necessity written by her doctor, twice. And so a third attempt was made.

Late documents

In December, Jessica received a peer-to-peer review request that was dated November 8, nearly a month prior. Her doctor did not receive the form at all. Because of the late arrival of the form, Jessica was told the window to have that review had closed.

Mysteriously, her letters to UHC were disappearing, and letters from UHC were arriving a month late or not at all.

Misidentified documents

The next option was to file an appeal. Jessica’s doctor filled out the appropriate form entitled “Grievances/Appeals.” After waiting the allotted time of 30 days for an appeal response, Jessica contacted UHC and was told that the document had been filed as a “grievance,” which meant it was “noted” with “no action taken.” She was instructed to make it clearer that it was in fact an appeal.

Her doctor wrote a second appeal, using the word “appeal” excessively to be sure it was clear what the document was. This was sent January 23, 2017. In September of 2016, when Jessica had initially filed, she’d already reached her deductible of $2600. In the new year, she’d have to reach that deductible again to get the new pump.

Misunderstanding of policy

February 2, 2017, the appeal was denied. This is what the denial from UHC said:

“There is not enough information in the records to show that your current pump and monitor are not working. Please submit a service letter from the supplier to show that the unit is broken and cannot be repaired.”

They also added: “This is only an interpretation of your Health Insurance Plan. It was based on the information that we were given and the language in your health plan. This is not intended to influence any decisions about your medical care.”

And yet it does, as Jessica can’t pay out-of-pocket $4-6,000 for a new pump, and she shouldn’t have to. She has health insurance.

On July 1, 2016, UnitedHealthcare chose Medtronic as its preferred insulin pump supplier. In an FAQ released by UnitedHealthcare, the insurance company assured its pump-using customers with this statement: “There is no immediate change to a member’s current pump. Members will continue using their existing device and supplies—regardless of the brand—until the insulin pump is out of warranty and needs to be replaced.”

Apparently, in the language used, “and” doesn’t mean that an out of warranty pump needs to be replaced. It instead signifies that in addition to being out of warranty, you have to prove “it needs to be replaced” … due to functionality failure.

Missing policy

If the pump breaks under warranty, the typical patient experience is that the supplier replaces it free of charge within a couple days. Due to UnitedHealthcare’s unclear policy, if the pump breaks outside of that warranty, Jessica is left with an undeterminable gap of time where she must negotiate with her insurer to cover a new pump. In the meantime, she must return to shots, which has consequences. “Without my pump,” explains Jessica, “I couldn’t meet the demands of my job caring for other people’s children and adults with disabilities.” UHC was given an opportunity to provide further comment and was unable to in advance of publication.

Beyond Type 1 asked UHC what their policy is for replacing an out-of-warranty pump and were told by Tracey Lempner, director of public relations at UHC, that finding that answer out in 24 hours was “a bit of a tight deadline.” Later, she told us, “It depends on the policy so there may be no broad or typical procedure.”

It’s surprising that there isn’t a uniform policy on navigating diabetes and insulin pumps. It’s even more surprising that neither UHC nor Jessica would have easy access to her personal policy. Jessica contacted customer service to inquire about that policy, this is what they said:

HOFFER: Hi! I am looking into my insulin pump coverage. I found DME information but it says to look under “diabetes services” and I can’t find where that is located

Jeffrey B.: I can help you with that. It will be just a moment while I access your benefits.

HOFFER: and actually it’s for Jessica.

Jeffrey B.: Thank you, sir.

Jeffrey B.: The category for diabetes services is not available on myuhc.com. It is only available for customer care agents.

HOFFER: is there any way you could email that policy to me? I would like to print it out so we can look at it together.

HOFFER: or regular mail?

Jeffrey B.: I can’t email the benefit information or mail it to you but I can copy-paste the part of diabetes services that is important to you in our chat?

HOFFER: that would be great. thank you

The portion of the internal document copied and pasted did support UHC’s claim to replace the pump only if broken:

“for necessary DME are only covered when required to make an item/device serviceable.” It did not, however, stipulate what Jessica would have to do if the pump broke—what the procedure would be to replace it and the timeframe involved.

We thought it strange that policy details were not readily available to Jessica, a paying customer. For someone who manages a chronic illness, having no guidelines for replacing a device to her medical care is understandably a cause of considerable distress.

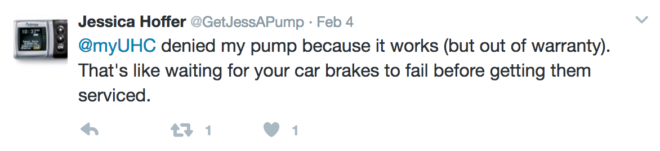

Frustrated, Jessica launched a social media campaign to share her story. On her Twitter account, @GetJessAPump, she shared:

Beyond being distressed by UHC’s policy and the efforts it took to find it, denying a replacement of an out-of-warranty pump is detrimental to Jessica’s healthcare and wellbeing. As a company, losing documents, delivering documents late, misfiling documents, mislabeling and crafting policies with misleading language, then making those policies difficult to find, is not only irresponsible, it’s unethical.

We, at Beyond Type 1, believe health insurance companies should provide transparent and easy to understand guidelines that promote the health and well being of their customers. If you agree, here’s how you can join us to help Jessica, protect yourself, and contribute to Beyond Type 1’s efforts to affect change:

How to HELP

Speak up: TWEET. Mention @myuhc + @beyondtype1, use hashtag #AccessMatters in the tweet, say something about why this issue matters to the Type 1 community – the critical necessity of insulin pump, the hassle of insurance and denials, the cost of supplies, etc. Repeat daily (or more!).

Help yourself – talk with your team. Understand what is in your policy, reach out to your insurance company and ask what happens when your pump warranty expires. Explain why replacing a pump promptly is critical.

Share your story: E-mail access@beyondtype1.org—send us your stories about navigating insurance denials and the lengths that we go to in order to receive the treatment prescribed by doctors.

Give to Access Fund: As of today, Beyond Type 1 has created an Access Fund. 100 percent of donations made to this fund will be used to aggressively address issues of access that people living with type 1 are faced with daily.

For further inquires about this article, email editor@beyondtype1.org.

Read more about Access issues in the United States and Globally.