Making It Look Easy

A new grasp

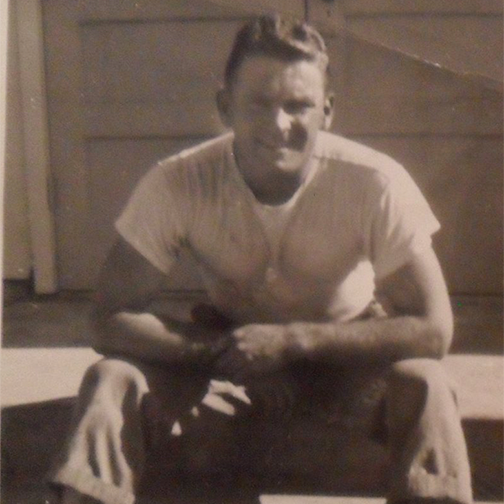

Growing up, I didn’t understand my grandfather’s diabetes, but I knew it was as much a part of his life as his career in the law. Although he eventually relegated his FBI badge to his sock drawer, he never took off his silver medical bracelet. And then there were his toes, several of which were removed when I was in elementary school.

Yes, my grandfather was right: Diabetes was a “raw deal.” But even so, there were still Redskins games to bet on and grandkids to tease. It wasn’t until a decade after his passing, when I was serving as a coast guard officer in Puerto Rico, that I learned that we shared a different bond.

I was on leave for New Year’s when I first knew something wasn’t right. As my parents and I drove across snowy New Hampshire to my sister’s house, we had to stop several times so I could use the bathroom. And then during dinner, I couldn’t stop drinking limeade. Paul Newman smiled back at me from the carton as if he were in on some kind of joke. I didn’t get it, though.

Three weeks later, my wife visited me in Puerto Rico. We spent Friday on my rooftop in Old San Juan. Saturday and Sunday were wide open. Maybe we would hit the beach in Luquillo or drive up the Pork Highway.

We didn’t do either.

My thirst had only gotten worse, and after consulting with Dr. Google, I bought a glucometer. That Saturday, feeling inexplicably hungover, I decided it was time. I pressed the test strip to the drop of blood and waited.

287—three times too high. My heart started pounding.

“You try it,” I said to my wife. “Maybe it’s not calibrated.”

She pricked her finger. 83. Perfect. We were at El Hospital de Veteranos an hour later. We had barely sat down before a gregarious nurse repeated the test.

“Diabetes,” he said, scratching his head. “But you seem too old for type 1 and too fit for type 2. We’ll see what the doctor thinks.”

Editor’s Note: You can get type 1 diabetes at any age and more than half of diagnoses are among people 18 and over.

My wife and I returned to our seats. We were supposed to be at the beach listening to reggaetón. After two hours, I had to escape that suffocating waiting room. We stepped into the afternoon humidity and found a concrete bench. I put my arm around my wife and watched paramedics unload an old veteran from an ambulancía. I took a deep breath, and my wife squeezed my hand.

“It’ll be okay,” she said, wiping a tear. “Your grandfather had diabetes. And you always say he lived a full life.” She was right. I saw my grandfather’s blue eyes and heard his Bronx accent. I thought about how I would be following in his footsteps—albeit ones without toes—and laughed.

How it is

In the two years since that afternoon at Veteranos, I haven’t lost any toes, but I have lost my job. The coast guard told me I couldn’t sail with my shipmates, and the gears of bureaucracy began grinding toward my medical retirement.

A week after the diagnosis, I drove to Mayagüez. My shipmates had been patrolling the Mona Passage for drug smugglers and migrants, and I needed to empty my stateroom. I wasn’t prepared for what I found, though. There were new jokes, new sea stories and a new executive officer. I pretended it didn’t bother me as I stepped onto the pier with my seabag over my shoulder and glucose tablets in my pocket.

Mine were orange flavored, since those were the ones that my grandfather kept in the console of his Camry. We both needed them in case we injected too much insulin.

Speaking of, while the advent of the pen needle means that I can surreptitiously inject myself, my grandfather lived in the syringe era. He would produce his kit with so much fanfare, often just before a family dinner, that one expected a trumpeter to announce the procedure’s commencement. He would inspect the syringe in the light, undo his belt, and plunge the needle into his belly. If we were lucky, he would happily let fly a litany of curse words, almost always involving some unseen “miserable bastard.”

Like a lot of people with diabetes, my grandfather also suffered from bouts of hypoglycemia. One day, my sister and I walked to his house and saw his “lady friend’s” Cadillac parked in front. Shirley met us at the door and told us that our grandfather was recuperating from an episode. I climbed the stairs to his bedroom and peered in.

My grandfather, usually a dapper dresser, sat on his bed in a rumpled undershirt, his gold Celtic cross dangling down his chest. He stared at the beige carpet. Physically he was there, but that was it. I crept away.

My first low occurred back at my parent’s house. My sister had purchased a badminton set for our nieces and nephews, and she and her husband challenged me and my wife to a couples match. For an hour, we took a break from adulthood to swat at a plastic cone. I began feeling lightheaded, but it wasn’t until my brother-in-law began scoring with ease that I ducked into the house to check my number. 43. My wife and mom hovered over me. “I’m fine,” I said, hands shaking. “I just need some orange juice.”

That was what my grandfather always drank.

That badminton match reminded me of playing Wiffle Ball with my older brothers. After mowing our grandfather’s lawn and pulling weeds, we would take turns pitching and batting. My grandfather would heckle us from the shade of the right field hedge row, a glass of Glenlivet in hand. My older brothers would hit home runs over the house and whiz curveballs across the plate. What I couldn’t match with skill, I matched with effort, diving at every chance.

“Look at the kid,” my grandfather would cackle. “He’s all ass and elbows. He needs to learn how to make it look easy!”

When my diabetes comes up in conversation, people offer their sympathy. “It’s fine,” I say. “It’s manageable.”

What I don’t tell them is that I knew a guy who made it look easy, a guy who’s still with me every time I prick my finger or jab a needle into my belly.