Survivor’s Guilt: Losing My Brother to DKA

Editor’s Note: For support navigating life after a type 1 death, please visit Jesse Was Here, a unique program of Beyond Type 1, providing resources to spouses, siblings, grandparents and friends in need.

I was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes (T1D) when I was 8 years old. I was about to attend a new school, and within the last few weeks of summer, I found myself learning to dose a medication responsible for being my lifeline. This diagnosis meant injecting needles I’d hope wouldn’t hurt every single time, and pricking my fingers at least four times a day. Although it was a heavy reality, I felt like I didn’t have time to react poorly. I just needed to learn how to keep myself alive every day. At 8 years old, that’s a daunting task, but I tried to carry the responsibility with strong shoulders and usually had the perspective that it could’ve been worse. When I was diagnosed, I shared a hospital room with a girl about the same age. She was practically in a full-body cast from a tragic car accident. Later, I found out that her family had all died in the accident, but she didn’t know that yet. Learning how to inject myself didn’t seem so bad with my family surrounding me and knowing I’d be returning to the comfort of my home soon. I found myself thankful, and almost 30 years later, I often reflect on how T1D has changed my life in countless ways.

A steep learning curve

My first experience with diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is still quite memorable. I had the flu and suddenly couldn’t stop throwing up in the middle of the night. I remember being in the dark, on my bed, with my mom holding a washcloth to my head and my older brother staring at me; he was there for support but also worried about me. I hadn’t been this sick since I was diagnosed, and I knew this wasn’t normal. Even though I felt so horrible, I was unwilling to go to the ER when my mom said it was time to go. I was just scared. After a lesson of what DKA was and its seriousness, I felt like it was my fault. I didn’t want to talk about it when I was finally released, and that guilt remained with me, resulting in not much conversation about it.

My family took the approach that they didn’t want me to feel abnormal or too different than any other children, and I felt like I had to be independent and take care of myself. That led to me not sharing too much about my T1D, and I just got used to managing it. Even though my brother and I shared an extraordinary relationship, I felt like my T1D separated us because he didn’t truly understand what I battled every day. That all changed, though, when he was diagnosed at age 22.

Ties that bind

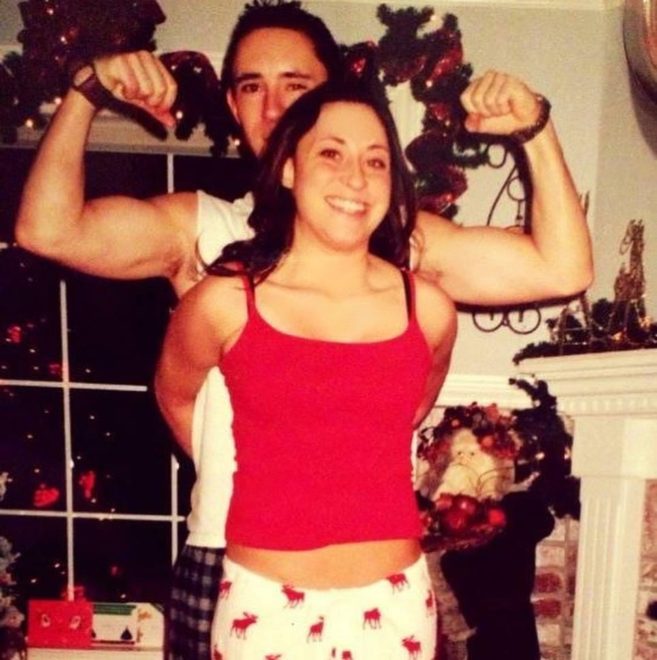

I vividly remember him calling me and saying, “I can’t believe my baby sister has been such a badass all these years, and I didn’t even realize what you had to do every day!” I laughed but was relieved I could share this flood of thoughts, feelings and frustrations with my big brother. Even though I got to share all these conversations with him, I had such a mix of emotions learning he was diagnosed. I cried for him because I knew what he would have to live with, but I also felt like we could be each other’s strongest ally. We had a tradition of calling each other every time we left the pharmacy and joked about the insanity of costs associated with keeping ourselves alive. Nick’s sense of humor often saved me from negativity, something I’m always grateful for.

But DKA found its way to Nick, too. He had just recently fought off the flu, and I had told him to make sure to stay hydrated. The flu returned, and he called me on a Sunday, his normal routine. I was stuffing my wedding invitations with my best friend, and our call was short. He told me he didn’t feel good and was tired. I told him again to stay hydrated, I loved him, and to call me when he felt better. A couple of days later, that call came instead from my sister-in-law telling me Nick had suffered a heart attack and was in a coma. After an agonizing flight across the country to get to him, the doctors ultimately explained he suffered too much brain damage, that he had no brain activity, and told us the dreaded “there’s nothing else we can do.” His cause of death was DKA, which led to a heart attack and brain damage. Nick was only 28. He had two small children and his whole family were supposed to be at my wedding in just two months. He had a lifetime of happiness ahead of him, and DKA took him quickly, without any remorse.

I had severe survivor’s guilt. I felt it should’ve been me, I didn’t have kids to live for, and I had been hospitalized for DKA a few times and survived. I had T1D much longer than Nick, and I should’ve told him a billion times how important it was to be extra vigilant when he got sick. I couldn’t believe it took his life. I felt angry that we didn’t treat my disease differently when I was growing up; it should’ve been more of a topic of conversation rather than taking the tactic of protecting my feelings so I didn’t feel different. An emergency plan should’ve always been in place as opposed to having to just react to a bad situation. Nick’s lack of health insurance at the time shouldn’t have impacted any of his decision making. I should’ve told my sister-in-law over and over again how important it was to pay attention to his health and get him treatment immediately if he was sick. Death from DKA is preventable, and I knew that more than most.

Stronger now

My 30-year milestone of living with T1D is upon me. I am now married and have a child of my own. Since Nick’s death, I made some dramatic changes to my management of the disease. After years of resistance, I committed to an insulin pump because I knew it would drastically help my overall health. I even dedicated myself to clinical trials for different devices and went beyond my comfort zone for the sake of improving T1D options. I found my way to the best endocrinologist I’ve ever had, even though her office is two hours away. I talk much more openly about my disease and share my frustrations with my incredibly supportive husband as I still try to balance the reality that T1D is mine forever, with no breaks, days off, or cures in sight. And even though Nick’s death may make it seem obvious that T1D and DKA are explicitly fragile, I’ve made sure to have emergency supplies and plans in place with my family. Nick will forever impact me and influence my choices. It’s easy to take so much for granted, but I promise you it’s sobering with just the mere memory of holding Nick’s hand in the hospital begging him not to leave us. Even though we are now separated by heaven and earth, T1D has made me stronger, and I have Nick to thank for that.

Jesse Was Here, a program of Beyond Type 1, is supported by the JDRF – Beyond Type 1 Alliance.