Life with Type 1—A Photo Essay

When I began dating my husband Tom I couldn’t have told you the purpose of the pancreas, let alone the difference between type 1 and type 2 diabetes. An ever-growing epidemic in the United States, type 2 is typically the result of diet and lifestyle choices and is largely preventable. It’s a disease that we’ve unfortunately become accustomed to hearing about on a regular basis. But what about the millions in this country living with type 1? They seem to have been lost in the discussion.

Both diseases are a result of problems with insulin, one of the hormones the body uses to regulate blood sugar and derive energy from food. But that’s where similarities end. Very simply put, type 2 diabetes has to do with insulin resistance. The pancreas produces it, but the body doesn’t use the insulin properly. Type 2 can be managed through a combination of diet, exercise and medication before (if ever) resorting to insulin injections. Meanwhile type 1 is an autoimmune disease (often diagnosed early in life—in Tom’s case at 2 years old) in which the pancreas stops producing insulin altogether. People with type 1 diabetes rely on insulin injections to lower blood sugar. Insulin is not a cure; it simply allows a person with type 1 to stay alive.

The complications of type 1 diabetes are grave, both short and long term. Administering too much insulin can cause low blood glucose (hypoglycemia), which can lead to seizures, coma and in extreme circumstances, death. On the opposite end of the spectrum, not enough insulin can cause very high blood glucose which can lead to diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), a life-threatening condition in which the blood becomes too acidic. The potential long-term complications are equally terrifying: blindness, kidney failure and limb amputation to name a few.

Life with type 1 is a perpetual and exhausting tightrope act. The goal is to achieve optimal blood glucose levels without going too high or too low. But despite constant finger pricks to check/re-check blood sugar, meticulous dosage and timing of insulin boluses, counting carbs and considering a myriad of other factors, it is virtually impossible to mimic the human pancreas. Factors that impact blood sugar include and are not limited to: all food (healthy or unhealthy), stress, imperfect timing and/or dosage of insulin, dehydration, exercise, weather, sleep (too much or lack of), inconsistent schedule, hormones, caffeine, illness … the list goes on.

Tempering my anxiety over Tom’s disease while being a supportive (but not overbearing) partner is something I work at on a daily basis. Lows in particular are a constant struggle for me. After having the disease for over 33 years, Tom has developed a dangerous condition called hypoglycemic unawareness in which he can no longer feel the symptoms (shakiness, lightheadedness) that serve to warn of a dropping blood sugar. I worry he’ll go too low while he’s driving, while he’s sleeping, when I’m not there. I worry about everything.

I often think about how unfair it is that people with type 1 diabetes never get a break from the burden of such complex, unrelenting disease. One can’t take a pill and forget about it for a few hours. Imagine having to manage a disease without a rulebook—it behaves differently for each person and under each circumstance. Type 1 requires attention and action 24/7, so it’s easy to understand how one might feel burned out or isolated. I’ve told my husband that I wish I could take his place, even for a single day, so he could know the freedom of life without having to think about blood sugar.

All this being said, to know Tom is to know the happiest guy on the planet. I marvel at his strength, his commitment to his health (particularly when it’s not easy, which is most of the time), his childlike joy for life. His absolute refusal to give in to bitterness. Every single day with Tom is filled with adventure and belly laughs. Yes, type 1 is always there, looming, but never able to define him. He won’t let it.

Documenting life with type 1 has been cathartic for me, and I hope can bring some awareness (however small) to the plight of all people with type 1 diabetes and their families.

A small tattoo on Tom’s right forearm with big meaning. It’s an homage to his lifeblood: C257H383N65O77S6 is the chemical formula for the synthetic insulin he has taken for the majority of his life.

Tom filling up the reservoir of his insulin pump, which he must wear at all times. Tubing connects the pump to an insertion site on his stomach (the site needs to be moved around every few days to avoid scar tissue buildup). At the insertion site is a tiny cannula that delivers the insulin directly into his bloodstream. A healthy pancreas constantly produces basal insulin (meaning a low dose, baseline) every few minutes, 24 hours a day, and automatically increases/decreases the amount it makes based on the current amount of glucose already in the blood. It also produces bolus insulin (meaning a larger amount) when the body requires more insulin to cover the increased amount of glucose in the bloodstream when a person eats. A healthy pancreas does a remarkable job of monitoring the exact amount of insulin needed to match the glucose that enters the blood. With type 1 diabetes, the pancreas cannot produce basal or bolus insulin, so synthetic insulin must be administered either by injection, or in Tom’s case, with a pump.

The question of course, is how much insulin. The pump has been a life-changing piece of technology for Tom and so many others; until he was 15 years old he had to administer manual injections to himself. It’s important to remember, however, that the insulin pump is not an intelligent device. While it makes administering the insulin much easier, Tom must still make the decisions as far as dosing.

The contents of Tom’s diabetes supply cabinet. It isn’t entirely clear what triggers the onset of type 1 diabetes. Researchers have discovered that genetics play a role; there is an inherited predisposition. They do not, however, know exactly what sets off the immune system causing it to turn against itself and destroy the insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas. Unlike type 2, type 1 diabetes has nothing to do with diet or lifestyle and is typically diagnosed during childhood.

Keeping my anxiety in check while Tom sleeps can be difficult for me. Is he just sleeping in? Is he conscious? Is he taking a nap because he’s genuinely tired or because he’s lethargic due to a low? I admit my worry has gotten the best of me many times. Early on in our relationship, I found myself waking him up to deliver pressing messages like “look how cute the dog is being right now” just to make sure he wasn’t dangerously low or unconscious. Needless to say, that approach didn’t go over well. Type 1 is a disease that affects the whole family, and I’m still very much a-work-in-progress when it comes to determining when is appropriate for me to act as caretaker and when I’m overstepping boundaries and need to let go.

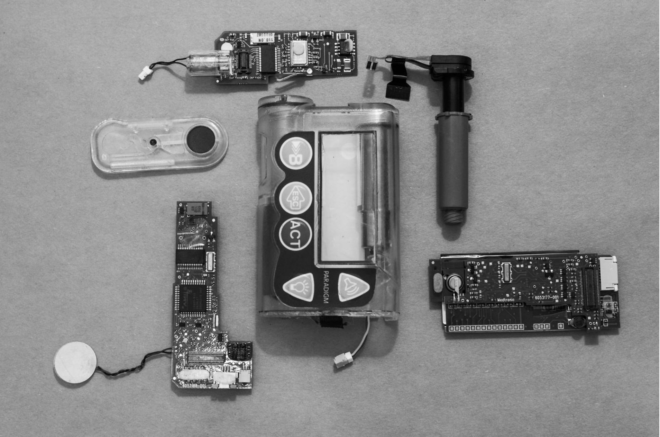

One of the insulin pumps Tom has used over the 21 years he’s been pumping. Once it was retired, we decided to take it apart for a look at the innards. Just like this old one, his new pump is routinely mistaken for a pager and it cracks us up every time.

Here Tom is inserting the sensor for his continuous glucose monitor, or CGM. A tiny electrode measures the blood glucose levels in tissue fluid every five minutes. It is connected to a transmitter that sends the information via wireless radio frequency to a monitoring and display device. This recent technology has been a game changer in his management of type 1. Not only does it give Tom a ballpark idea of where his blood sugar is at, but an alarm on the monitor will sound when certain levels (high or low) are reached. The CGM is not 100 percent accurate by any means (there’s a lag when glucose moves from blood to tissue fluid so it’s not quite real time) and it doesn’t replace finger pricks (it constantly needs to be calibrated with them), but is a useful tool and potential safety net. The CGM alarm sounding like a fog horn at 3 a.m. is always a jarring, but a welcome, disruption from sleep … at least to me.

Between constant finger pricks and in the above case, accidentally hitting a blood vessel during CGM sensor insertion, it’s hard for people with type 1 diabetes not to feel like a pin cushion at times.

Type 1 is an invisible, misunderstood disease. Things people often say to Tom: “You don’t look like you have diabetes,” “But you’re thin,” “Can you eat that?”, “That stinks you can’t have sugar.” Many erroneously lump type 1 diabetes together with type 2, which is understandable (and something I did before I met Tom) due to the fact that they share the same name. Many type 1 advocates, myself included, feel that the diseases should be differentiated with unique names. There’s already so much confusion surrounding the facts about diabetes, it would help raise awareness and benefit those living with both type 1 and type 2 if the public were better informed.

Tom filling his pump with insulin and priming the tubing before insertion.

Our days are filled with yo-yoing numbers, and this is one that we don’t like to see. 65 is low enough to require treatment with fast-acting carbohydrates. I sometimes find myself hovering over the meter when Tom does a finger prick, trying to get a glimpse of the number. While my intentions are of course good, it’s important to remind myself to respect Tom’s space and his ability to manage it on his own. It’s his body, after all, and he survived most of his life just fine without me. I once heard type 1 likened to a stepchild for a spouse, a comparison that resonated with me. While it will always be a part of my life and it’s important for me to be involved to a certain extent, type 1 will always be Tom’s baby and his alone.

Juice boxes are the go-to treatment for lows so Tom knows exactly how many carbs he’s taking in with each one.

Tom participating as a subject in an artificial pancreas study at the University of Chicago. Researchers are working to develop an algorithm that links the insulin pump to the CGM, while automatically delivering the appropriate amount of insulin making it a fully automated process. The artificial pancreas could potentially ease the burden of people with type 1 diabetes in a monumental way, allowing them not to have to think about their blood glucose 24/7. It wouldn’t be a cure, but the next best thing.

Apple juice to the rescue.

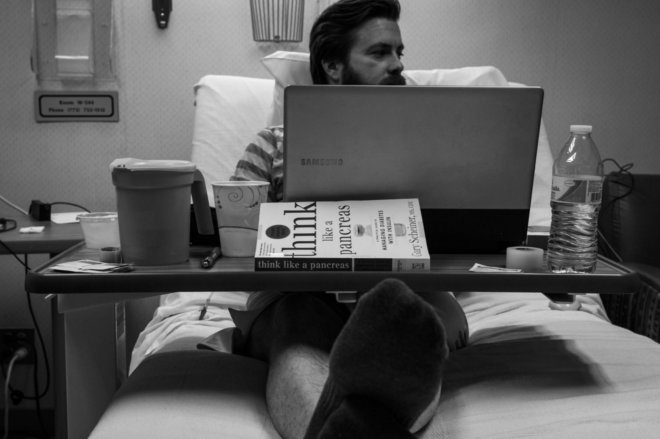

Tom spent 72 hours in the hospital monitoring his blood sugar every five minutes, with a team of researchers sitting beside the bed (even while he slept) working on the algorithm.

The unicorn: a constant straight line of stable blood sugar readings on Tom’s CGM monitor.

Type 1 is a cruel, demanding disease. You can do everything right and still get an inexplicable blood sugar. It’s easy to blame yourself, get down about it and stress about the potential complications. What’s more important, as Tom has taught me, is to live life on your own terms. The straight line above is yes, something to be celebrated, but not something to be expected on an average day with type 1. That’s the thing, there IS no average day. All you can do is your best, and meanwhile enjoy life.

This article was originally published on Anne Marie Moran’s blog.

Want to spread awareness? Become an ambassador at Beyond Type 1. Click the button to learn all the ways you can become involved in Beyond Type 1’s global community!