What I Learned from a Summer at Diabetes Camp

Shortly after my diagnosis with type I diabetes, I pretended to shoot up heroin in the bathroom for the amusement of my friends. It went like this: lean back against a stall, inject insulin into the lower triceps, and moan something about “the good stuff.” I would excuse myself from class to do this, too embarrassed to shoot up in front of everybody.

My embarrassment surprised me. Months before, it would not have occurred to me to think of diabetes as a source of shame, or even as something particularly abnormal. Now, at 15, I was diagnosed and my attitude changed.

I grew up surrounded by the disease. Both of my brothers were diagnosed before me, and our early lives were littered with test strips and syringes. Familiarity bled diabetes of its mystery and menace. I became used to seeing beads of blood appear on my brothers’ fingers; until I held the pricker between my own, I didn’t understand how this act could make others squeamish. Similarly, I was indifferent to the sight of needles being thrust into arms, thighs and stomachs. But soon, I would learn that injecting insulin tends to draw attention. Pull out a syringe, and the eyes of classmates swarm to it instantly.

Teachers shot me looks of annoyance when I pricked my finger under my desk, and I got red in the face when they called me out for eating glucose in class. But when they learned I was a person with diabetes, and offered to make an exception for me, it was somehow worse. In this situation, not only does the unwanted attention bring discomfort, but you don’t think you deserve or even want the pity. The embarrassment of the person with diabetes, then, becomes hermetic and unassailable. It’s embarrassing to take care of the disease, and your embarrassment is itself embarrassing, because you don’t want it to be a big deal.

So instead of dealing with the mild mortification of injecting insulin during class, I turned it into something to laugh at. At parties, when people asked me what those syringes in my hand were for, I would respond with a significant look and a wink. Vague embarrassment in the classroom turned into making jokes about doing smack in the bathroom. Soon it became difficult to take diabetes seriously—growing up with it had normalized the disease, and making jokes about it obscured the dire reality.

That’s the thing about diabetic life. Somehow you trick yourself into thinking it’s not a big deal.

There was one place my brothers used to go where type 1 diabetes was no big deal—but it was also the only deal: Diabetes Camp.

Nestled in the hills of south Tennessee, Diabetes Camp distinguished itself to parents with its emphasis on encouraging kids to take care of their own condition. Rather than trying to give kids a break from diabetes, this camp wanted their campers to embrace the responsibility of their own treatment.

My older brother Mason was diagnosed when he was 5, and my little brother William was diagnosed when he was 9. I wasn’t diagnosed until 15, so I never went as a camper. They went every summer to wield needles boldly, prick fingers in public, and generally escape the ambient low-level embarrassment of diabetic life. I stayed home.

The camp held semi-mythic status for my brothers, mainly due to the prank wars. My brothers tried other diabetes summer camps, but this particular camp was the coolest. To hear them tell it, other camps resembled prisons, with hawkish overbearing adults, and this one resembled nothing so much as a two-week Anglo-Saxon blood feud. In a good way.

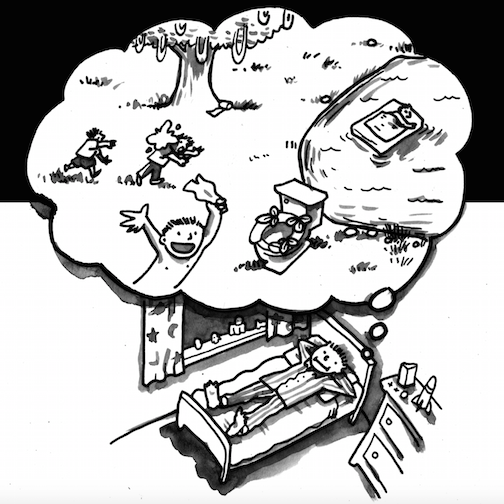

Campers pitched battles with shaving-cream balloons, and the losers retaliated with nocturnal raids, achieving varying degrees of ruthlessness. Their opponents awoke on air mattresses drifting on the lake, and the feud would continue. Kids brought rags from home, carefully selected and rolled into rat-tails. They returned to their parents at the end of camp with oozing wounds covering their legs, barely scabbed over.

William crossed a line in the prank wars one year by rubbing poison ivy leaves on toilet seats. Lax as diabetes camp was, it was this prank that finally earned him temporary exile: his sentence for the crime was being forced to return home early. For him, the exit was vaguely triumphant, and he was able to return the next summer.

Needless to say, diabetes camp sounded Valhallic. But until I was 20, I never went, and so the concept of diabetic community remained abstract. Before my diagnosis I envied my brothers the two weeks during which they disappeared to Tennessee. They participated in a mythos I could not touch.

When, as a counselor, I finally had a chance to go, I didn’t know what to expect from a community of people with diabetes. The chaos surprised me. Here was a village of screaming unscrupulous children with tubes in their bellies and needles in their pockets. During dodge ball, kids wolfed glucose tablets and leapt back into the game, sugar flying from their mouths. Others sat by, enduring the unsublime suffering of hyperglycemia, while their friends ribbed them for their testiness. Campers sweated test strips, and the fields and floors bespoke the messiness of diabetic life.

But this mess didn’t feel shameful. The diabetic detritus wasn’t all mine, and it served as a constant reminder of the community roiling around me. At any moment I might see somebody chugging juice with frantic low-blood sugar eyes, or irritably wringing blood out of a finger. It became difficult to see my disease as a unique experience, or something to be borne alone. At camp, diabetes didn’t isolate anyone. It was what everyone had in common.

Over time, checking my blood sugar stopped feeling like drudgery. The campers would have competitions, trying to see who could keep their blood sugars in the target range the longest. In this context, it was fun to be mocked by strangers for low blood sugar, or to provoke laughter for a grumpy high blood sugar. It wasn’t like when I pretended to my friends that my insulin was heroin. There was levity, but it did not spring from a desire to hide my own embarrassment.

In my experience, there is a tension between the dire and the blasé when you have type 1 diabetes. This tension makes it difficult to think about. It’s a serious disease, but not one that feels conducive to fear or self-pity. It can kill you quickly if you make a mistake, or slowly if you are negligent, but largely it’s a disease that bores rather than frightens. Checking blood sugar five to seven times per day, administering insulin for meals: these actions are fraught with mortal consequences, but it’s difficult to feel their weight. Instead, it’s all too easy to become numb to the cold stream of data that comprises the day-to-day mundanity of diabetic life. Taking care of your diabetes feels like having to remember to breathe—it’s tedious and perhaps slightly degrading, but you don’t expect anyone to feel sorry for you.

That doesn’t mean, however, that there’s nothing to be sorry about. That’s another thing I learned in Tennessee. Camp showed that diabetic life could be fun, but it was still deadly serious. One day, William was teaching archery when he noticed a little girl sitting in the weeds, refusing to participate. She was sulking. He went to comfort her, expecting to hear a story about fighting or bullying, friends being mean. If only it was that easy to fix. The girl had just gotten off the phone with her parents—she’d just heard for the first time that she had kidney disease.

Writing about diabetes, like talking about it, is difficult. You can’t find meaning or coherence in it, at least not easily. It is too serious to be dismissed, but its sufferers don’t need the rhetoric of strength or survival. It feels normal, but it isn’t. Too easily, I slip into a kind of fraught armistice with the disease, forgetting its dangers and resenting only its dreariness.

But that village of screaming kids with diabetes kicked me out of my uneasy indifference. Their bleeding fingers, those snapping rat-tails and the reek of bottled insulin everywhere eroded my embarrassment, while the mess of needles and strips chastened my sense of isolation. Nobody had to explain when they produced a syringe, and nobody had to hide their glucose tablets under a desk. For a few weeks, diabetes camp became a panaceas for a condition too mild to complain about but too persistent to defeat.

More importantly, it reminded me that I don’t have to pretend to do smack in the bathroom to give myself insulin. Unless I want to.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published on Folks.

Learn more about Diabetes Camp and how to attend.